6.2 KiB

Lecture 26 --- C++ Inheritance and Polymorphism

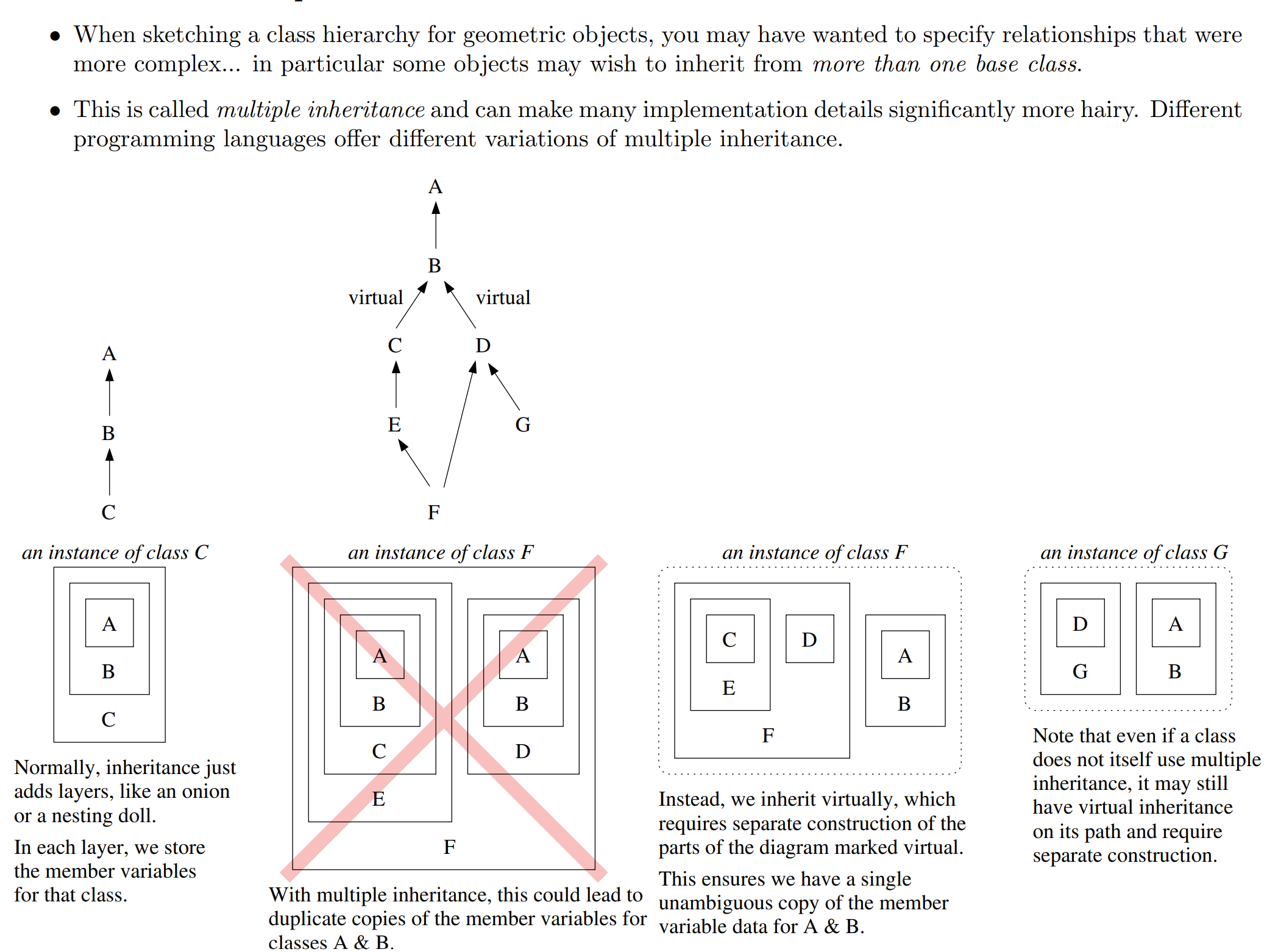

26.1 Multiple Inheritance

-

Multiple inheritance allows a class to inherit from more than one base class.

-

Note:

26.2 The Diamond Problem

- The Diamond Problem occurs in multiple inheritance when two classes inherit from the same base class, and a fourth class inherits from both of those.

\`\`\` Human / \ Student Worker \ / CSStudent \`\`\`

- Both Student and Worker inherit from Human.

class Human {

public:

void speak();

};

class Student : public Human {};

class Worker : public Human {};

class CSStudent : public Student, public Worker {};

-

CSStudent inherits from both Student and Worker.

-

Compiler sees two Human base classes.

-

This leads to duplicate data and ambiguous member resolution.

CSStudent cs;

cs.speak(); // ❌ Ambiguous: which Human::speak()?

Solution: Virtual Inheritance

- Use the virtual keyword when inheriting the common base class.

class Student : virtual public Human {};

class Worker : virtual public Human {};

class CSStudent : public Student, public Worker {};

CSStudent cs;

cs.speak(); // ✅ No ambiguity

-

How it works:

-

Compiler ensures only one shared instance of Human.

-

Student and Worker do not create their own copies of Human.

-

Memory layout uses pointers behind the scenes to share the base.

-

Constructor Order with Virtual Inheritance

When virtual inheritance is involved:

Most derived class (e.g., CSStudent) is responsible for calling the base (Human) constructor.

class Human {

public:

Human(int age) {}

};

class Student : virtual public Human {

public:

Student() : Human(0) {} // ❌ Not allowed to call Human(int) here

};

class CSStudent : public Student {

public:

CSStudent() : Human(21), Student() {} // ✅ Human constructor called here

};

26.2 Introduction to Polymorphism

- Let’s consider a small class hierarchy version of polygonal objects:

class Polygon {

public:

Polygon() {}

virtual ~Polygon() {}

int NumVerts() { return verts.size(); }

virtual double Area() = 0;

virtual bool IsSquare() { return false; }

protected:

vector<Point> verts;

};

class Triangle : public Polygon {

public:

Triangle(Point pts[3]) {

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) verts.push_back(pts[i]); }

double Area();

};

class Quadrilateral : public Polygon {

public:

Quadrilateral(Point pts[4]) {

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) verts.push_back(pts[i]); }

double Area();

double LongerDiagonal();

bool IsSquare() { return (SidesEqual() && AnglesEqual()); }

private:

bool SidesEqual();

bool AnglesEqual();

};

- Functions that are common, at least have a common interface, are in Polygon.

- Some of these functions are marked virtual, which means that when they are redefined by a derived class, this new definition will be used, even for pointers to base class objects.

- Some of these virtual functions, those whose declarations are followed by = 0 are pure virtual, which means

they must be redefined in a derived class.

– Any class that has pure virtual functions is called “abstract”.

– Objects of abstract types may not be created — only pointers to these objects may be created. - Functions that are specific to a particular object type are declared in the derived class prototype.

26.3 A Polymorphic List of Polygon Objects

- Now instead of two separate lists of polygon objects, we can create one “polymorphic” list:

std::list<Polygon*> polygons;

- Objects are constructed using new and inserted into the list:

Polygon *p_ptr = new Triangle( .... );

polygons.push_back(p_ptr);

p_ptr = new Quadrilateral( ... );

polygons.push_back(p_ptr);

Triangle *t_ptr = new Triangle( .... );

polygons.push_back(t_ptr);

Note: We’ve used the same pointer variable (p_ptr) to point to objects of two different types.

26.4 Accessing Objects Through a Polymorphic List of Pointers

- Let’s sum the areas of all the polygons:

double area = 0;

for (std::list<Polygon*>::iterator i = polygons.begin(); i!=polygons.end(); ++i){

area += (*i)->Area();

}

Which Area function is called? If *i points to a Triangle object then the function defined in the Triangle class would be called. If *i points to a Quadrilateral object then Quadrilateral::Area will be called.

- Here’s code to count the number of squares in the list:

int count = 0;

for (std::list<Polygon*>::iterator i = polygons.begin(); i!=polygons.end(); ++i){

count += (*i)->IsSquare();

}

If Polygon::IsSquare had not been declared virtual then the function defined in Polygon would always be called! In general, given a pointer to type T we start at T and look “up” the hierarchy for the closest function definition (this can be done at compile time). If that function has been declared virtual, we will start this search instead at the actual type of the object (this requires additional work at runtime) in case it has been redefined in a derived class of type T.

- To use a function in Quadrilateral that is not declared in Polygon, you must “cast” the pointer. The pointer *q will be NULL if *i is not a Quadrilateral object.

for (std::list<Polygon*>::iterator i = polygons.begin(); i!=polygons.end(); ++i) {

Quadrilateral *q = dynamic_cast<Quadrilateral*> (*i);

if (q) std::cout << "diagonal: " << q->LongerDiagonal() << std::endl;

}

26.5 Exercise

What is the output of the following program?

#include <iostream>

class Base {

public:

Base() {}

virtual void A() { std::cout << "Base A "; }

void B() { std::cout << "Base B "; }

};

class One : public Base {

public:

One() {}

void A() { std::cout << "One A "; }

void B() { std::cout << "One B "; }

};

class Two : public Base {

public:

Two() {}

void A() { std::cout << "Two A "; }

void B() { std::cout << "Two B "; }

};

int main() {

Base* a[3];

a[0] = new Base;

a[1] = new One;

a[2] = new Two;

for (unsigned int i=0; i<3; ++i) {

a[i]->A();

a[i]->B();

}

std::cout << std::endl;

return 0;

}

26.6 Exercise

What is the output of the following program?