Lecture 6 --- Pointer and Dynamic Memory

- Different types of memory

- Dynamic allocation of arrays

6.1 Three Types of Memory

- Automatic memory: memory allocation inside a function when you create a variable. This allocates space for local variables in functions (on the stack) and deallocates it when variables go out of scope. For example:

int x;

double y;

- Static memory: variables allocated statically (with the keyword static). They are are not eliminated when they go out of scope. They retain their values, but are only accessible within the scope where they are defined. For example:

static int counter;

- Dynamic memory: explicitly allocated (on the heap) as needed. This is our focus for today.

6.2 Dynamic Memory

Dynamic memory is:

- created using the new operator,

- accessed through pointers, and

- removed through the delete operator. Here’s a simple example involving dynamic allocation of integers:

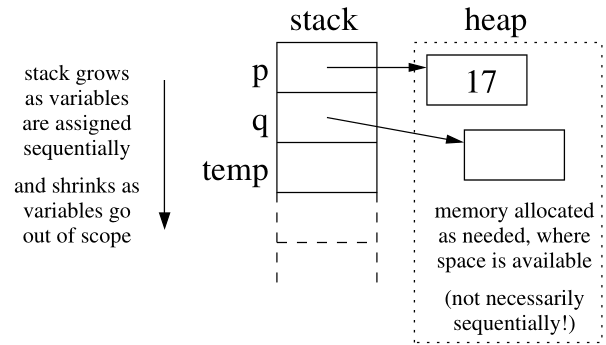

- The expression new int asks the system for a new chunk of memory that is large enough to hold an integer and returns the address of that memory. Therefore, the statement

int * p = new int;

allocates memory from the heap and stores its address in the pointer variable p.

- The statement

delete p;

takes the integer memory pointed by p and returns it to the system for re-use.

-

This memory is allocated from and returned to a special area of memory called the heap. By contrast, local variables and function parameters are placed on the stack.

-

In between the new and delete statements, the memory is treated just like memory for an ordinary variable, except the only way to access it is through pointers. Hence, the manipulation of pointer variables and values is similar to the examples covered in the pointers lecture except that there is no explicitly named variable for that memory other than the pointer variable.

-

Dynamic allocation of primitives like ints and doubles is not very interesting or significant. What’s more important is dynamic allocation of arrays and class objects.

-

Play this animation to see what exactly the above code snippet does.

6.3 Dynamic Allocation of Arrays

- How do we allocate an array on the stack? What is the code? What memory diagram is produced by the code?

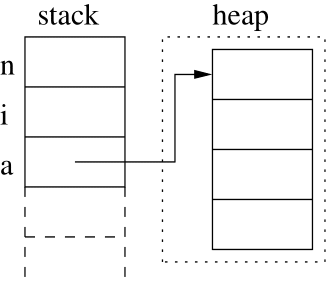

- Declaring the size of an array at compile time doesn’t offer much flexibility. Instead we can dynamically allocate an array based on data. This gets us part-way toward the behavior of the standard library vector class. Here’s an example:

-

The expression new double[n] asks the system to dynamically allocate enough consecutive memory to hold n double’s (usually 8n bytes).

- What’s crucially important is that n is a variable. Therefore, its value and, as a result, the size of the array are not known until the program is executed and the the memory must be allocated dynamically.

- The address of the start of the allocated memory is assigned to the pointer variable a.

-

After this, a is treated as though it is an array. For example: a[i] = sqrt( i ); In fact, the expression a[i] is exactly equivalent to the pointer arithmetic and dereferencing expression *(a+i) which we have seen several times before.

-

After we are done using the array, the line: delete [] a; releases the memory allocated for the entire array and calls the destructor (we’ll learn about these soon!) for each slot of the array. Deleting a dynamically allocated array without the [] is an error (but it may not cause a crash or other noticeable problem, depending on the type stored in the array and the specific compiler implementation).

-

Since the program is ending, releasing the memory is not a major concern. However, to demonstrate that you understand memory allocation & deallocation, you should always delete dynamically allocated memory in this course, even if the program is terminating.

-

In more substantial programs it is ABSOLUTELY CRUCIAL. If we forget to release memory repeatedly the program can be said to have a memory leak. Long-running programs with memory leaks will eventually run out of memory and crash.

-

Play this animation to see what exactly the above code snippet does.

6.4 Dynamic Allocation of Two-Dimensional Arrays

To store a grid of data, we will need to allocate a top level array of pointers to arrays of the data. For example:

double** a = new double*[rows];

for (int i = 0; i < rows; i++) {

a[i] = new double[cols];

for (int j = 0; j < cols; j++) {

a[i][j] = double(i+1) / double (j+1);

}

}

-

Draw a picture of the resulting data structure.

-

Then, write code to correctly delete all of this memory.

-

Play this animation to see what exactly the above code snippet does.

6.5 Dynamic Allocation: Arrays of Class Objects

We can dynamically allocate arrays of class objects. The default constructor (the constructor that takes no arguments) must be defined in order to allocate an array of objects.

class Foo {

public:

Foo();

double value() const { return a*b; }

private:

int a;

double b;

};

Foo::Foo() {

static int counter = 1;

a = counter;

b = 100.0;

counter++;

}

int main() {

int n;

std::cin >> n;

Foo *things = new Foo[n];

std::cout << "size of int: " << sizeof(int) << std::endl;

std::cout << "size of double: " << sizeof(double) << std::endl;

std::cout << "size of foo object: " << sizeof(Foo) << std::endl;

for (Foo* i = things; i < things+n; i++)

std::cout << "Foo stored at: " << i << " has value " << i->value() << std::endl;

delete [] things;

}

The above program will produce the following output:

size of int: 4

size of double: 8

size of foo object: 16

Foo stored at: 0x104800890 has value 100

Foo stored at: 0x1048008a0 has value 200

Foo stored at: 0x1048008b0 has value 300

Foo stored at: 0x1048008c0 has value 400

...

6.6 Exercises

6.7 Memory Debugging

In addition to the step-by-step debuggers like gdb, lldb, or the debugger in your IDE, we recommend using a memory debugger like “Dr. Memory” (Windows, Linux, and MacOSX) or “Valgrind” (Linux and MacOSX). These tools can detect the following problems:

- Use of uninitialized memory

- Reading/writing memory after it has been free’d (NOTE: delete calls free)

- Reading/writing off the end of malloc’d blocks (NOTE: new calls malloc)

- Reading/writing inappropriate areas on the stack

- Memory leaks - where pointers to malloc’d blocks are lost forever

- Mismatched use of malloc/new/new [] vs free/delete/delete []

- Overlapping src and dst pointers in memcpy() and related functions

6.8 Sample Buggy Program

Can you see the errors in this program?

1 #include <iostream>

2

3 int main() {

4

5 int *p = new int;

6 if (*p != 10) std::cout << "hi" << std::endl;

7

8 int *a = new int[3];

9 a[3] = 12;

10 delete a;

11

12 }

6.9 Using Dr. Memory http://www.drmemory.org

Here’s how Dr. Memory reports the errors in the above program:

~~Dr.M~~ Dr. Memory version 1.8.0

~~Dr.M~~

~~Dr.M~~ Error #1: UNINITIALIZED READ: reading 4 byte(s)

~~Dr.M~~ # 0 main [memory_debugger_test.cpp:6]

hi

~~Dr.M~~

~~Dr.M~~ Error #2: UNADDRESSABLE ACCESS beyond heap bounds: writing 4 byte(s)

~~Dr.M~~ # 0 main [memory_debugger_test.cpp:9]

~~Dr.M~~ Note: refers to 0 byte(s) beyond last valid byte in prior malloc

~~Dr.M~~

~~Dr.M~~ Error #3: INVALID HEAP ARGUMENT: allocated with operator new[], freed with operator delete

~~Dr.M~~ # 0 replace_operator_delete [/drmemory_package/common/alloc_replace.c:2684]

~~Dr.M~~ # 1 main [memory_debugger_test.cpp:10]

~~Dr.M~~ Note: memory was allocated here:

~~Dr.M~~ Note: # 0 replace_operator_new_array [/drmemory_package/common/alloc_replace.c:2638]

~~Dr.M~~ Note: # 1 main [memory_debugger_test.cpp:8]

~~Dr.M~~

~~Dr.M~~ Error #4: LEAK 4 bytes

~~Dr.M~~ # 0 replace_operator_new [/drmemory_package/common/alloc_replace.c:2609]

~~Dr.M~~ # 1 main [memory_debugger_test.cpp:5]

~~Dr.M~~

~~Dr.M~~ ERRORS FOUND:

~~Dr.M~~ 1 unique, 1 total unaddressable access(es)

~~Dr.M~~ 1 unique, 1 total uninitialized access(es)

~~Dr.M~~ 1 unique, 1 total invalid heap argument(s)

~~Dr.M~~ 0 unique, 0 total warning(s)

~~Dr.M~~ 1 unique, 1 total, 4 byte(s) of leak(s)

~~Dr.M~~ 0 unique, 0 total, 0 byte(s) of possible leak(s)

~~Dr.M~~ Details: /DrMemory-MacOS-1.8.0-8/drmemory/logs/DrMemory-a.out.7726.000/results.txt

And the fixed version:

~~Dr.M~~ Dr. Memory version 1.8.0

hi

~~Dr.M~~

~~Dr.M~~ NO ERRORS FOUND:

~~Dr.M~~ 0 unique, 0 total unaddressable access(es)

~~Dr.M~~ 0 unique, 0 total uninitialized access(es)

~~Dr.M~~ 0 unique, 0 total invalid heap argument(s)

~~Dr.M~~ 0 unique, 0 total warning(s)

~~Dr.M~~ 0 unique, 0 total, 0 byte(s) of leak(s)

~~Dr.M~~ 0 unique, 0 total, 0 byte(s) of possible leak(s)

~~Dr.M~~ Details: /DrMemory-MacOS-1.8.0-8/drmemory/logs/DrMemory-a.out.7762.000/results.txt

Note: Dr. Memory on Windows with the Visual Studio compiler may not report a mismatched free() / delete / delete [] error (e.g., line 10 of the sample code above). This may happen if optimizations are enabled and the objects stored in the array are simple and do not have their own dynamically-allocated memory that lead to their own indirect memory leaks.

6.10 Using Valgrind http://valgrind.org/

And this is how Valgrind reports the same errors:

==31226== Memcheck, a memory error detector

==31226== Copyright (C) 2002-2013, and GNU GPL'd, by Julian Seward et al.

==31226== Using Valgrind-3.9.0 and LibVEX; rerun with -h for copyright info

==31226== Command: ./a.out

==31226==

==31226== Conditional jump or move depends on uninitialised value(s)

==31226== at 0x40096F: main (memory_debugger_test.cpp:6)

==31226==

hi

==31226== Invalid write of size 4

==31226== at 0x4009A3: main (memory_debugger_test.cpp:9)

==31226== Address 0x4c3f09c is 0 bytes after a block of size 12 alloc'd

==31226== at 0x4A0700A: operator new[](unsigned long) (in /usr/lib64/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==31226== by 0x400996: main (memory_debugger_test.cpp:8)

==31226==

==31226== Mismatched free() / delete / delete []

==31226== at 0x4A07991: operator delete(void*) (in /usr/lib64/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==31226== by 0x4009B4: main (memory_debugger_test.cpp:10)

==31226== Address 0x4c3f090 is 0 bytes inside a block of size 12 alloc'd

==31226== at 0x4A0700A: operator new[](unsigned long) (in /usr/lib64/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==31226== by 0x400996: main (memory_debugger_test.cpp:8)

==31226==

==31226==

==31226== HEAP SUMMARY:

==31226== in use at exit: 4 bytes in 1 blocks

==31226== total heap usage: 2 allocs, 1 frees, 16 bytes allocated

==31226==

==31226== 4 bytes in 1 blocks are definitely lost in loss record 1 of 1

==31226== at 0x4A06965: operator new(unsigned long) (in /usr/lib64/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==31226== by 0x400961: main (memory_debugger_test.cpp:5)

==31226==

==31226== LEAK SUMMARY:

==31226== definitely lost: 4 bytes in 1 blocks

==31226== indirectly lost: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==31226== possibly lost: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==31226== still reachable: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==31226== suppressed: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==31226==

==31226== For counts of detected and suppressed errors, rerun with: -v

==31226== Use --track-origins=yes to see where uninitialised values come from

==31226== ERROR SUMMARY: 4 errors from 4 contexts (suppressed: 2 from 2)

And here’s what it looks like after fixing those bugs:

==31252== Memcheck, a memory error detector

==31252== Copyright (C) 2002-2013, and GNU GPL'd, by Julian Seward et al.

==31252== Using Valgrind-3.9.0 and LibVEX; rerun with -h for copyright info

==31252== Command: ./a.out

==31252==

hi

==31252==

==31252== HEAP SUMMARY:

==31252== in use at exit: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==31252== total heap usage: 2 allocs, 2 frees, 16 bytes allocated

==31252==

==31252== All heap blocks were freed -- no leaks are possible

==31252==

==31252== For counts of detected and suppressed errors, rerun with: -v

==31252== ERROR SUMMARY: 0 errors from 0 contexts (suppressed: 2 from 2)

6.11 How to use a memory debugger

- Detailed instructions on installation & use of these tools are available here: http://www.cs.rpi.edu/academics/courses/fall23/csci1200/memory_debugging.php

- Memory errors (uninitialized memory, out-of-bounds read/write, use after free) may cause seg faults, crashes, or strange output.

- Memory leaks on the other hand will never cause incorrect output, but your program will be inefficient and hog system resources. A program with a memory leak may waste so much memory it causes all programs on the system to slow down significantly or it may crash the program or the whole operating system if the system runs out of memory (this takes a while on modern computers with lots of RAM & harddrive space).

- For many future homeworks, Submitty will be configured to run your code with Dr. Memory to search for memory problems and present the output with the submission results. For full credit your program must be memory error and memory leak free!

- A program that seems to run perfectly fine on one computer may still have significant memory errors. Running a memory debugger will help find issues that might break your homework on another computer or when submitted to the homework server.

- Important Note: When these tools find a memory leak, they point to the line of code where this memory was allocated. These tools does not understand the program logic and thus obviously cannot tell us where it should have been deleted.

- A final note: STL and other 3rd party libraries are highly optimized and sometimes do sneaky but correct and bug-free tricks for efficiency that confuse the memory debugger. For example, because the STL string class uses its own allocator, there may be a warning about memory that is “still reachable” even though you’ve deleted all your dynamically allocated memory. The memory debuggers have automatic suppressions for some of these known “false positives”, so you will see this listed as a “suppressed leak”. So don’t worry if you see those messages.

6.12 Diagramming Memory Exercises

- Draw a diagram of the heap and stack memory for each segment of code below. Use a “?” to indicate that the value of the memory is uninitialized. Indicate whether there are any errors or memory leaks during execution of this code.

class Foo {

public:

double x;

int* y;

};

Foo a;

a.x = 3.14159;

Foo *b = new Foo;

(*b).y = new int[2];

Foo *c = b;

a.y = b->y;

c->y[1] = 7;

b = NULL;

int a[5] = { 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 };

int *b = a + 2;

*b = 7;

int *c = new int[3];

c[0] = b[0];

c[1] = b[1];

c = &(a[3]);

Write code to produce this diagram: