16 KiB

Lecture 22 --- Hash Tables

Today’s Lecture

- Hash Tables, Hash Functions, and Collision Resolution

- Performance of: Hash Tables vs. Binary Search Trees

- Collision resolution: separate chaining vs open addressing

- STL’s unordered_set and unordered_map

- Using a hash table to implement a set/map

22.1 Definition: What’s a Hash Table?

- A table implementation with constant time access.

- Like a set, we can store elements in a collection. Or like a map, we can store key-value pair associations in the hash table. But it’s even faster to do find, insert, and erase with a hash table! However, hash tables do not store the data in sorted order.

- A hash table is implemented with an array at the top level.

- Each element or key is mapped to a slot in the array by a hash function.

22.2 Definition: What’s a Hash Function?

- A simple function of one argument (the key) which returns an integer index (a bucket or slot in the array).

- Ideally the function will “uniformly” distribute the keys throughout the range of legal index values (0 → k-1).

- What’s a collision?

- When the hash function maps multiple (different) keys to the same index.

- How do we deal with collisions?

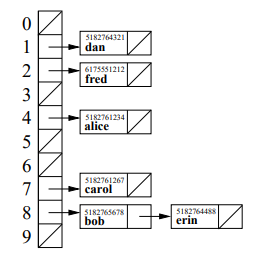

- One way to resolve this is by storing a linked list of values at each slot in the array.

22.3 Example: Caller ID

- We are given a phonebook with 50,000 name/number pairings. Each number is a 10 digit number. We need to create a data structure to lookup the name matching a particular phone number. Ideally, name lookup should be O(1) time expected, and the caller ID system should use O(n) memory (n = 50,000).

- Note: In the toy implementations that follow we use small datasets, but we should evaluate the system scaled up to handle the large dataset.

- The basic interface:

// add several names to the phonebook

add(phonebook, 1111, "fred");

add(phonebook, 2222, "sally");

add(phonebook, 3333, "george");

// test the phonebook

std::cout << identify(phonebook, 2222) << " is calling!" << std::endl;

std::cout << identify(phonebook, 4444) << " is calling!" << std::endl;

22.4 Caller ID with an STL Vector

// create an empty phonebook

std::vector<std::string> phonebook(10000, "UNKNOWN CALLER");

void add(std::vector<std::string> &phonebook, int number, std::string name) {

phonebook[number] = name;

}

std::string identify(const std::vector<std::string> &phonebook, int number) {

return phonebook[number];

}

Exercise: What's the memory complexity for the vector-based Caller ID system? What's the expected runtime complexity for identify, insert, and erase?

22.5 Caller ID with an STL Map

// create an empty phonebook

std::map<int,std::string> phonebook;

void add(std::map<int,std::string> &phonebook, int number, std::string name) {

phonebook[number] = name;

}

std::string identify(const std::map<int,std::string> &phonebook, int number) {

map<int,std::string>::const_iterator tmp = phonebook.find(number);

if (tmp == phonebook.end()){

return "UNKNOWN CALLER";

}else{

return tmp->second;

}

}

Exercise: What's the memory complexity for the map-based Caller ID system? What's the expected runtime complexity for identify, add, and erase?

22.6 Now let's implement Caller ID with a Hash Table

#define PHONEBOOK_SIZE 10

class Node {

public:

int number;

string name;

Node* next;

};

// create the phonebook, initially all numbers are unassigned

Node* phonebook[PHONEBOOK_SIZE];

for (int i = 0; i < PHONEBOOK_SIZE; i++) {

phonebook[i] = NULL;

}

// corresponds a phone number to a slot in the array

int hash_function(int number) {

}

// add a number, name pair to the phonebook

void add(Node* phonebook[PHONEBOOK_SIZE], int number, string name) {

}

// given a phone number, determine who is calling

std::string identify(Node* phonebook[PHONEBOOK_SIZE], int number) {

}

Play this animation to understand how this works.

22.7 Exercise: Hash Table Performance

-

What's the memory complexity for the hash-table-based Caller ID system?

-

What's the expected runtime complexity for identify, insert, and erase?

22.8 What makes a Good Hash Function?

- Deterministic – same input always produces the same hash.

- Goals: fast O(1) computation and a random, uniform distribution of keys throughout the table, despite the actual distribution of keys that are to be stored.

- For example, using: f(k) = abs(k)%N as our hash function satisfies the first requirement, but may not satisfy the second.

- Another example of a dangerous hash function on string keys is to add or multiply the ascii values of each char:

unsigned int hash(const std::string& k, unsigned int N) {

unsigned int value = 0;

for (unsigned int i=0; i<k.size(); ++i) {

value += k[i]; // conversion to int is automatic

}

return value % N;

}

The problem is its high collision rate:

-

Anagrams (e.g., "listen" and "silent") get the same hash.

-

Many different strings can sum to the same value, leading to collisions.

- This can be improved through multiplications that involve the position and value of the key:

unsigned int hash(const std::string& k, unsigned int N) {

unsigned int value = 0;

for (unsigned int i=0; i<k.size(); ++i) {

value = value*31 + k[i]; // conversion to int is automatic

}

return value % N;

}

-

The 2nd method is better, but can be improved further. The theory of good hash functions is quite involved and beyond the scope of this course.

-

You can run this program hash_test.cpp which will show that the second hash function produces a lower collision rate:

$ g++ -Wall -Wextra hash_test.cpp

$ ./a.out

Testing badHash (Summing ASCII values):

Total Collisions: 4914

Execution Time: 0.000142 seconds

Testing betterHash (Multiplication by 31, a prime):

Total Collisions: 4000

Execution Time: 0.000148 seconds

22.9 How do we Resolve Collisions? METHOD 1: Separate Chaining

- Each table location stores a linked list of keys (and values) hashed to that location (as shown above in the phonebook hashtable). Thus, the hashing function really just selects which list to search or modify.

- This works well when the number of items stored in each list is small, e.g., an average of 1. Other data structures, such as binary search trees, may be used in place of the list, but these have even greater overhead considering the (hopefully, very small) number of items stored per bin.

22.10 How do we Resolve Collisions? METHOD 2: Open Addressing

-

In open addressing, when the chosen table location already stores a key (or key-value pair), a different table location is sought in order to store the new value (or pair).

-

Here are three different open addressing variations to handle a collision during an insert operation:

– Linear probing: If i is the chosen hash location then the following sequence of table locations is tested (“probed”) until an empty location is found:

(i+1)%N, (i+2)%N, (i+3)%N, ...

– Quadratic probing: If i is the hash location then the following sequence of table locations is tested:

(i+1)%N, (i+2*2)%N, (i+3*3)%N, (i+4*4)%N, ...

More generally, the jth “probe” of the table is (i + c1j + c2j2) mod N where c1 and c2 are constants.

– Secondary hashing: when a collision occurs a second hash function is applied to compute a new table location. This is repeated until an empty location is found.

-

For each of these approaches, the find operation follows the same sequence of locations as the insert operation. The key value is determined to be absent from the table only when an empty location is found.

-

When using open addressing to resolve collisions, the erase function must mark a location as “formerly occupied”. If a location is instead marked empty, find may fail to return elements in the table. Formerly occupied locations may (and should) be reused, but only after the find operation has been run to completion.

-

Problems with open addressing:

– Slows dramatically when the table is nearly full (e.g. about 80% or higher). This is particularly problematic for linear probing.

– Fails completely when the table is full.

– Cost of computing new hash values.

22.11 Hash Table in STL?

- The Standard Template Library standard and implementation of hash table have been slowly evolving over many years. Unfortunately, the names “hashset” and “hashmap” were spoiled by developers anticipating the STL standard, so to avoid breaking or having name clashes with code using these early implementations...

- STL’s agreed-upon standard for hash tables: unordered_set and unordered_map.

- You can use std::unordered_set the same way as you use std::set, even though the internal of these two are different, the external interface are the same.

- You can use std::unordered_map the same way as you use std::map, even though the internal of these two are different, the external interface are the same.

22.12 Leetcode Exercises

- Leetcode problem 1: Two Sum. Solution: p1_twosum_hash_table.cpp.

Note: make sure you understand this longest consecutive sequence problem and its solution, because you will re-write this function in the lab.